“The ASL tour videos on our YouTube channel remain some of the most viewed videos on the channel.”

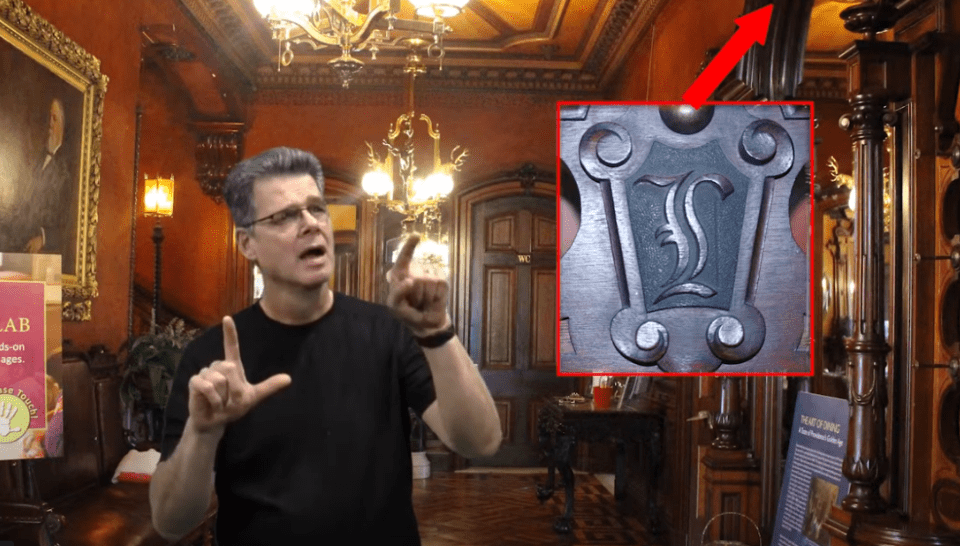

Providence’s historic Lippitt House Museum drew inspiration from its founding family in creating a American Sign Language (ASL) video tour with the help of a Sherlock Center Access for All Abilities Mini Grant.

Gov. Henry Lippitt’s daughter, Jeanie Lippitt Weeden, became deaf when she was 4 after scarlet fever. She later worked with her mother, Mary Ann Balch Lippitt, advocating for the public education of hearing-impaired children and both were instrumental in establishing the Rhode Island School for the Deaf.

Built in 1865 on the corner of Hope and Angell streets on the East Side, the Preserve Rhode Island property offer tours, special exhibitions, lectures, art installations, concerts and family programs.

Museum Director Carrie Taylor said increasing accessibility is an institutional priority. The museum had started the project with Tim Riker, senior lecturer in ASL at Brown University, and his class. In 2017, the museum sought the Sherlock Center grant to help implement the tour.

“We were particularly excited about an opportunity to work with members of the deaf and hard of hearing community, given the historical connection of the Lippitt family to deaf education in Rhode Island and specifically Mary Ann Lippitt’s involvement with the founding of the Rhode Island School for the Deaf in 1876,” she said.

They consulted native ASL speakers when developing the script before filming began. “It became apparent that for brevity’s sake, the content needed to stay to focused on the most important interpretive themes the English tour is based on – Providence’s industrial history, its immigration legacy and the significance of the exuberant design of the house,” she said. “This allows for explaining some of the English vocabulary that might be new to some ASL speakers but still convey the most important historical context Lippitt House Museum wants all visitors to come away with after a tour.”

As the project developed, they shared scripts and draft video recordings with native ASL speakers for suggestions and comments. They shortened both as a result of this feedback to make it easier for viewers to follow. They also sought advice about how to promote the tour to the ASL community and incorporated that into the marketing plan and on-site signs.

Taylor said the ASL tour covers the same themes as the English tour – who lived in this house (servants and family), what life was like for them, what was happening in Providence at the time and what that tells us about Providence today. The main difference, she said, is that the recorded ASL tour offers less interaction with staff.

One advantage is that the ASL videos can be viewed remotely, making them assessible anywhere. “ASL viewers can visit Lippitt House Museum virtually at any time and aren’t constrained to the museum’s open hours,” she said. And, while the pandemic has affected their overall visitation numbers, “the ASL tour videos on our YouTube channel remain some of the most viewed videos on the channel.”

The museum also has added a sensory piece to all in-person tours – a table of touchable objects from the museum’s teaching collection. Visitors are encouraged to handle and interact with the objects to explore and think about how they were made and used in the 19th century. Taylor said museum staff also recently met with Riker and an administrator from the Rhode Island School for the Deaf to discuss possible future collaborations.

Taylor said this project was not only an opportunity to increase accessibility, but also a learning experience for the staff. “The staff education element to gain greater knowledge about how to welcome and accommodate the needs of ASL visitors was very helpful,” she said.