“You can absolutely go to college. You are far better than you think you are. You are extraordinary. It’s not a problem, it’s a superpower.”

Students in Rhode Island College’s Certificate of Graduate Studies in Autism Education program gained valuable insights into how they can better support their students during a classroom visit from an autistic self-advocate.

Associate Professor Dr. Paul LaCava, co-teaching the graduate course “Building Social and Communication Skills” with adjunct faculty member Melynda Antunes, invited Malcolm Streitfeld, a RIC undergraduate anthropology major and staff writer for The Anchor student newspaper, to share his experiences and perspectives with the educators.

Students in the class, who all work with all ages of students in public and private schools, engaged in a dynamic exchange with Streitfeld, posing numerous questions to deepen their understanding of supporting students on the autism spectrum.

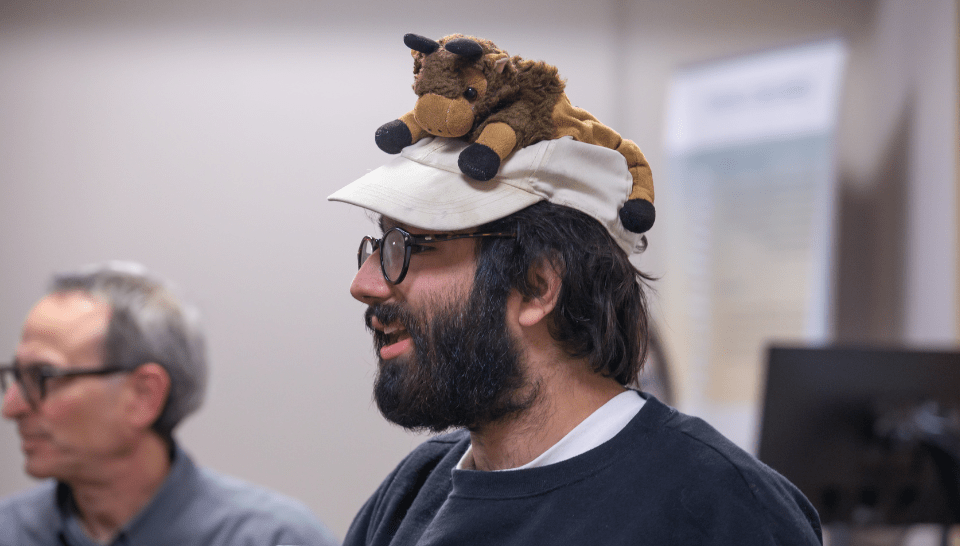

Streitfeld, wearing a hat with a stuffed buffalo figure he named Apple Crisp (“It’s part of my identity. I have an attachment to this hat that is special.”) said his diagnosis came between ages 7 and 9 after years of his parents taking him to many doctors. A neurologist referred the family to a therapist who specializes in autism, and she diagnosed him.

“Autism is a spectrum and I am diagnosed as high-functioning so I don’t struggle as much in social situations,” he said. “But because I’m autistic, my brain functions differently.”

One way, he said, is insomnia. “I can’t turn off my brain when I sleep. It doesn’t have an off switch.”

Another is sensory and information overload. “I can be overwhelmed by loud sounds around me and I need to take a break. Smells and sounds are something I experience more,” he said.

Streitfeld said his coping strategies include taking a walk, having some alone time in his room to get some space, taking a break from social interaction or finding an activity he can throw himself into.

“We all have selected interests we tend to get fixated on. We tend to hyperfocus on a task and tune out the world around us,” he said. “Like when I’m walking, I’m so focused on getting to my destination that I can forget about waiting for the crossing signal because I’m so determined to get there.” He said he also has lost track of time and forgotten to eat.

To help his insomnia, he has adopted a bedtime routine. “I take a shower to calm sensory, I read to calm my mind, exercise to calm my body and then do a muscle-relaxing sequence to calm my whole self down.”

He said as a child, his imaginary world often felt so real it was difficult to distinguish from reality. “My imagination is why I couldn’t give up my autism for anything,” he said.

“Autistic people can feel emotions. We’re not robots. In fact, it’s the opposite. We tend to feel compassion and empathy more.” He said it’s difficult to describe, but it’s almost as though he takes on the emotions of his friends. “I feel more, empathize more.”

He said making friends as a student in elementary and middle school was challenging. “I’m a very active social butterfly but I have a small group of friends. In younger grades, I felt isolated and bullied.” He said his self-awareness came through therapy. “As a child, I was aware kids were avoiding me, but I didn’t understand why.”

Students asked how teachers could have helped. “Communicating to the class and helping me develop friendships with other kids. In middle school, it would have been helpful for them to explain what autism is and why I’m different. They need to understand I’m not so different that I can’t bond with them.”

Streitfeld said he struggles with fine motor skills and coordination including tying shoes and garbage bags. A student asked how he overcomes this. “Lots of practice,” he said. “I have spent hours practicing things like tying shoes and garbage bags.”

He is working with his therapist on goals for life skills he doesn’t have. “I want to be skilled and capable to live on my own and not with my parents. I’m working toward that.” One of those goals is cooking independently.

He found managing finances challenging until his father, an accountant, hired a financial literacy tutor. He was overspending, but now has a stable bank account. He said he also has been taken advantage of; he lost first phone because a child took it after he borrowed it to call his mother. Another time he was swindled by someone who said he needed $20 for the train.

“Now I try to keep my head down and not interact with strangers, which is hard with this hat, especially!” he said.

Streitfeld doesn’t drive. “Because of autism, I’m very easily distracted and not confident in myself to learn to drive. I’m afraid I’m going to crash or won’t keep the car stable so I walk, ride the bus, catch rides with others and use Uber.”

He said he’s wanted to be a novelist and short story writer since a school visit from local storyteller Len Cabral inspired him be a writer. In his free time, he likes to take photos, read his poetry, play video games, take walks, hang out with his mom’s dogs (she’s a dog sitter) and listen to podcasts.

A student asked whether he struggles with social cues. “Reading the room is hard for me. People can’t tell if I’m joking. Communicating feelings is hard. I worry about how people react. I tend to over-apologize even when I haven’t done anything wrong,” he said. “We don’t have a good sense of boundaries. We tend to put too much of ourselves out there. We end up giving information about ourselves that’s far too personal. It’s something I still struggle with.”

How about facial expressions? “I still do have a hard time telling whether someone is serious or joking. If it’s too obtuse or subtle, it’s hard for us to pick up on.”

Text, email and social media also can prove challenging for him. “But that’s not just neurodiverse people. It’s hard to read what someone is thinking or feeling on the other side of the computer.”

What was it like hearing autism as a diagnosis? “I was a little nervous and a little curious. I wanted to understand what autism was. I have a natural propensity to learn and I wanted to learn why I was different.” And his family? “I can’t speak for them but I think they felt relieved. We had been to countless doctors who were not able to give a clear answer.”

A student asked what he would tell neurodivergent students who think they can’t go to college. “You can absolutely go to college. You are far better than you think you are. You are extraordinary. It’s not a problem, it’s a superpower.”